I had a great question submitted to me (thank you Brandman!) that I thought would make for a good blog post:

...I've been wondering if it really matters from a performance standpoint where I start my queries. For example, if I join from A-B-C, would I be better off starting at table B and then going to A & C?

The short answer: Yes. And no.

Watch this week's video on YouTube

Disclaimer: For this post, I'm only going to be talking about INNER joins. OUTER (LEFT, RIGHT, FULL, etc...) joins are a whole 'nother animal that I'll save for time.

Let's use the following query from WideWorldImporters for our examples:

/*

-- Run if if you want to follow along - add a computed column and index for CountryOfManufacture

ALTER TABLE Warehouse.StockItems SET (SYSTEM_VERSIONING = OFF);

ALTER TABLE Warehouse.StockItems

ADD CountryOfManufacture AS CAST(JSON_VALUE(CustomFields,'$.CountryOfManufacture') AS NVARCHAR(10))

ALTER TABLE Warehouse.StockItems SET (SYSTEM_VERSIONING = ON);

CREATE INDEX IX_CountryOfManufacture ON Warehouse.StockItems (CountryOfManufacture)

*/

SELECT

o.OrderID,

s.CountryOfManufacture

FROM

Sales.Orders o -- 73595 rows

INNER JOIN Sales.OrderLines l -- 231412 rows

ON o.OrderID = l.OrderID -- 231412 rows after join

INNER JOIN Warehouse.StockItems s -- 227 rows

ON l.StockItemID = s.StockItemID -- 1036 rows after join

AND s.CountryOfManufacture = 'USA' -- 8 rows for USA

Note: with an INNER join, I normally would prefer putting my 'USA' filter in the WHERE clause, but for the rest of these examples it'll be easier to have it part of the ON.

The key thing to notice is that we are joining three tables - Orders, OrderLines, and StockItems - and that OrderLines is what we use to join between the other two tables.

We basically have two options for table join orders then - we can join Orders with OrderLines first and then join in StockItems, or we can join OrderLines and StockItems first and then join in Orders.

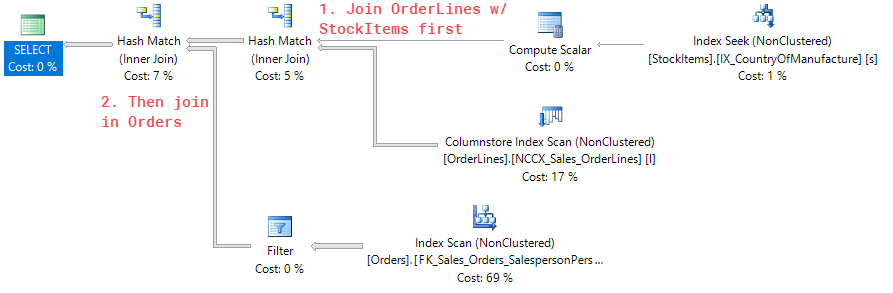

In terms of performance, it's almost certain that the latter scenario (joining OrderLines with StockItems first) will be faster because StockItems will help us be more selective.

Selective? Well you might notice that our StockItems table is small with only 227 rows. It's made even smaller by filtering on 'USA' which reduces it to only 8 rows.

Since the StockItems table has no duplicate rows (it's a simple lookup table for product information) it is a great table to join with as early as possible since it will reduce the total number of rows getting passed around for the remainder of the query.

If we tried doing the Orders to OrderLines join first, we actually wouldn't filter out any rows in our first step, cause our subsequent join to StockItems to be more slower (because more rows would have to be processed).

Basically, join order DOES matter because if we can join two tables that will reduce the number of rows needed to be processed by subsequent steps, then our performance will improve.

So if the order that our tables are joined in makes a big difference for performance reasons, SQL Server follows the join order we define right?

SQL Server doesn't let you choose the join order

SQL is a declarative language: you write code that specifies *what* data to get, not *how* to get it.

Basically, the SQL Server query optimizer takes your SQL query and decides on its own how it thinks it should get the data.

It does this by using precalculated statistics on your table sizes and data contents in order to be able to pick a "good enough" plan quickly.

So even if we rearrange the order of the tables in our FROM statement like this:

SELECT

o.OrderID,

s.CountryOfManufacture

FROM

Sales.OrderLines l

INNER JOIN Warehouse.StockItems s

ON l.StockItemID = s.StockItemID

AND s.CountryOfManufacture = 'USA'

INNER JOIN Sales.Orders o

ON o.OrderID = l.OrderID

Or if we add parentheses:

SELECT

o.OrderID,

s.CountryOfManufacture

FROM

(Sales.OrderLines l

INNER JOIN Sales.Orders o

ON l.OrderID = o.OrderID)

INNER JOIN Warehouse.StockItems s

ON l.StockItemID = s.StockItemID

AND s.CountryOfManufacture = 'USA'

Or even if we rewrite the tables into subqueries:

SELECT

l.OrderID,

s.CountryOfManufacture

FROM

(

SELECT

o.OrderID,

l.StockItemId

FROM

Sales.OrderLines l

INNER JOIN Sales.Orders o

ON l.OrderID = o.OrderID

) l

INNER JOIN Warehouse.StockItems s

ON l.StockItemID = s.StockItemID

AND s.CountryOfManufacture = 'USA'

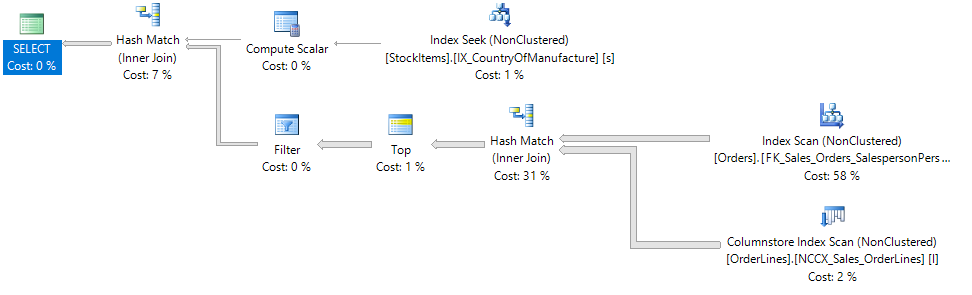

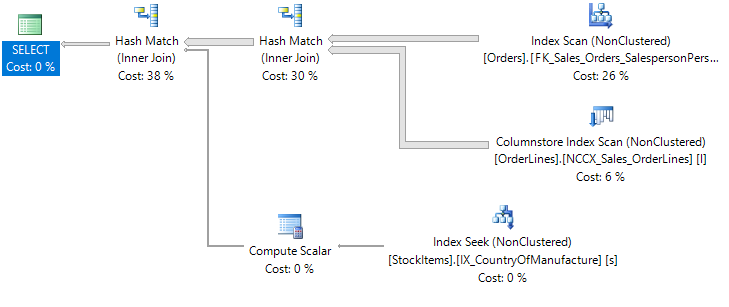

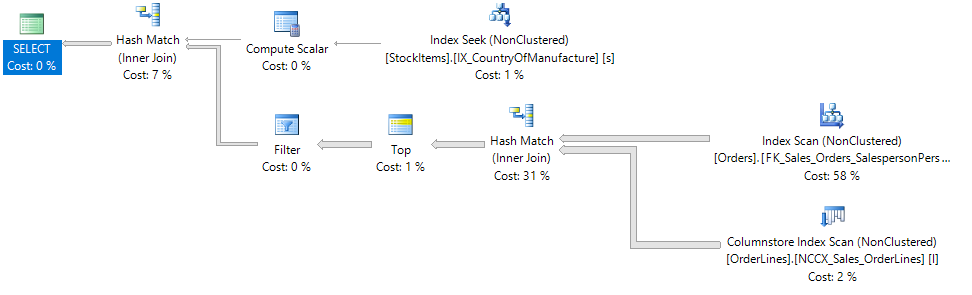

SQL Server will interpret and optimize our three separate queries (plus the original one from the top of the page) into the same exact execution plan:

Basically, no matter how we try to redefine the order of our tables in the FROM statement, SQL Server will still do what it thinks it's best.

But what if SQL Server doesn't know best?

The majority of the time I see SQL Server doing something inefficient with an execution plan it's usually due to something wrong with statistics for that table/index.

Statistics are also a whole 'nother topic for a whole 'nother day (or month) of blog posts, so to not get too side tracked with this post, I'll point you to Kimberly Tripp's introductory blog post on the subject: https://www.sqlskills.com/blogs/kimberly/the-accidental-dba-day-15-of-30-statistics-maintenance/)

The key thing to take away is that if SQL Server is generating an execution plan where the order of table joins doesn't make sense check your statistics first because they are the root cause of many performance problems!

Forcing a join order

So you already checked to see if your statistics are the problem and exhausted all possibilities on that front. SQL Server isn't optimizing for the optimal table join order, so what can you do?

Row goals

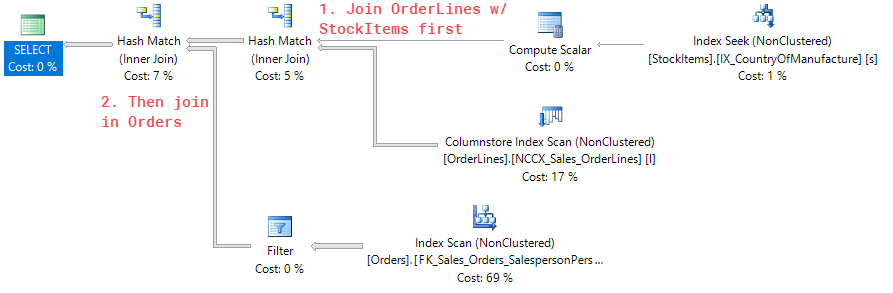

If SQL Server isn't behaving and I need to force a table join order, my preferred way is to do it via a TOP() command.

I learned this technique from watching Adam Machanic's fantastic presentation on the subject and I highly recommend you watch it.

Since in our example query SQL Server is already joining the tables in the most efficient order, let's force an inefficient join by joining Orders with OrderLines first.

**Basically, we write a subquery around the tables we want to join together first and make sure to include a TOP clause. **

SELECT

o.OrderID,

s.CountryOfManufacture

FROM

(

SELECT TOP(2147483647) -- A number of rows we know is larger than our table. Watch Adam's presentation above for more info.

o.OrderID,

l.StockItemID

FROM

Sales.Orders o

INNER JOIN Sales.OrderLines l

ON o.OrderID = l.OrderID

) o

INNER JOIN Warehouse.StockItems s

ON o.StockItemID = s.StockItemID

AND s.CountryOfManufacture = 'USA'

Including TOP forces SQL to perform the join between Orders and OrderLines first - inefficient in this example, but a great success in being able to control what SQL Server does.

This is my favorite way of forcing a join order because we get to inject control over the join order of two specific tables in this case (Orders and OrderLines) but SQL Server will still use its own judgement in how any remaining tables should be joined.

While forcing a join order is generally a bad idea (what happens if the underlying data changes in the future and your forced join no longer is the best option), in certain scenarios where its required the TOP technique will cause the least amount of performance problems (since SQL still gets to decide what happens with the rest of the tables).

The same can't be said if using hints...

Query and join hints

Query and join hints will successfully force the order of the table joins in your query, however they have significant draw backs.

Let's look at the FORCE ORDER query hint. Adding it to your query will successfully force the table joins to occur in the order that they are listed:

SELECT

o.OrderID,

s.CountryOfManufacture

FROM

Sales.Orders o

INNER JOIN Sales.OrderLines l

ON o.OrderID = l.OrderID

INNER JOIN Warehouse.StockItems s

ON l.StockItemID = s.StockItemID

AND s.CountryOfManufacture = 'USA'

OPTION (FORCE ORDER)

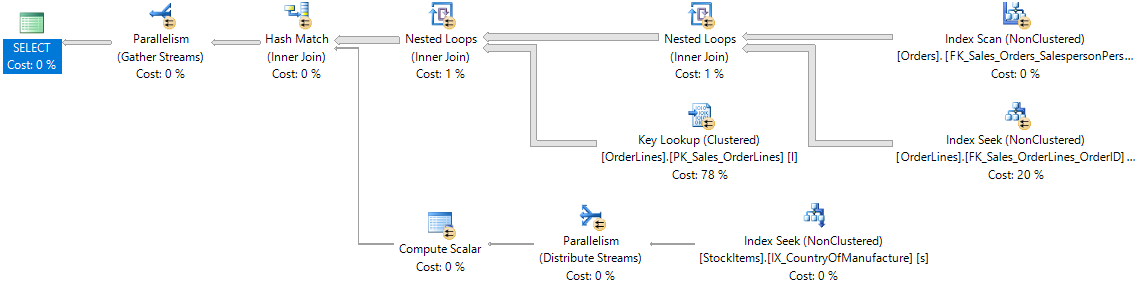

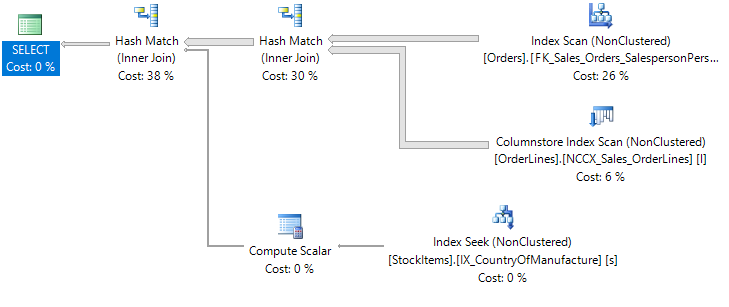

Looking at the execution plan we can see that Orders and OrderLines were joined together first as expected:

The biggest drawback with the FORCE ORDER hint is that all tables in your query are going to have their join order forced (not evident in this example...but imagine we were joining 4 or 5 tables in total).

This makes your query incredibly fragile; if the underlying data changes in the future, you could be forcing multiple inefficient join orders. Your query that you tuned with FORCE ORDER could go from running in seconds to minutes or hours.

The same problem exists with using a join hints:

SELECT

o.OrderID,

s.CountryOfManufacture

FROM

Sales.Orders o

INNER LOOP JOIN Sales.OrderLines l

ON o.OrderID = l.OrderID

INNER JOIN Warehouse.StockItems s

ON l.StockItemID = s.StockItemID

AND s.CountryOfManufacture = 'USA'

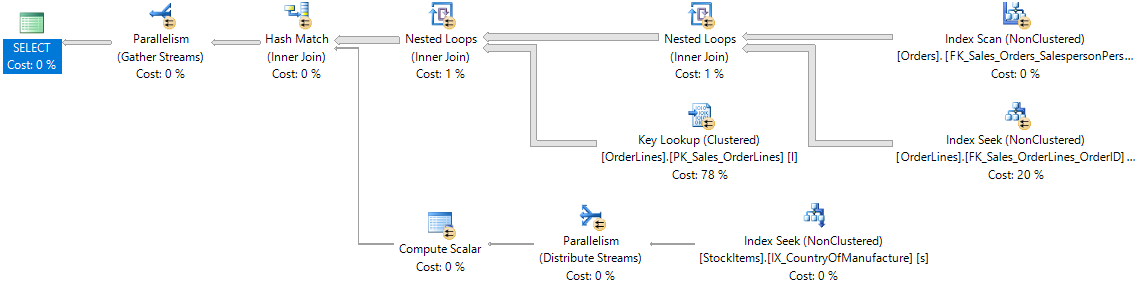

Using the LOOP hint successfully forces our join order again, but once again the join order of all of our tables becomes fixed:

A join hint is probably the most fragile hint that forces table join order because not only is it forcing the join order, but it's also forcing the algorithm used to perform the join.

In general, I only use query hints to force table join order as a temporary fix.

Maybe production has a problem and I need to get things running again; a query or join hint may be the quickest way to fix the immediate issue. However, long term using the hint is probably a bad idea, so after the immediate fires are put out I will go back and try to determine the root cause of the performance problem.

Summary

- Table join order matters for reducing the number of rows that the rest of the query needs to process.

- By default SQL Server gives you no control over the join order - it uses statistics and the query optimizer to pick what it thinks is a good join order.

- Most of the time, the query optimizer does a great job at picking efficient join orders. When it doesn't, the first thing I do is check to see the health of my statistics and figure out if it's picking a sub-optimal plan because of that.

- If I am in a special scenario and I truly do need to force a join order, I'll use the TOP clause to force a join order since it only forces the order of a single join.

- In an emergency "production-servers-are-on-fire" scenario, I might use a query or join hint to immediately fix a performance issue and go back to implement a better solution once things calm down.